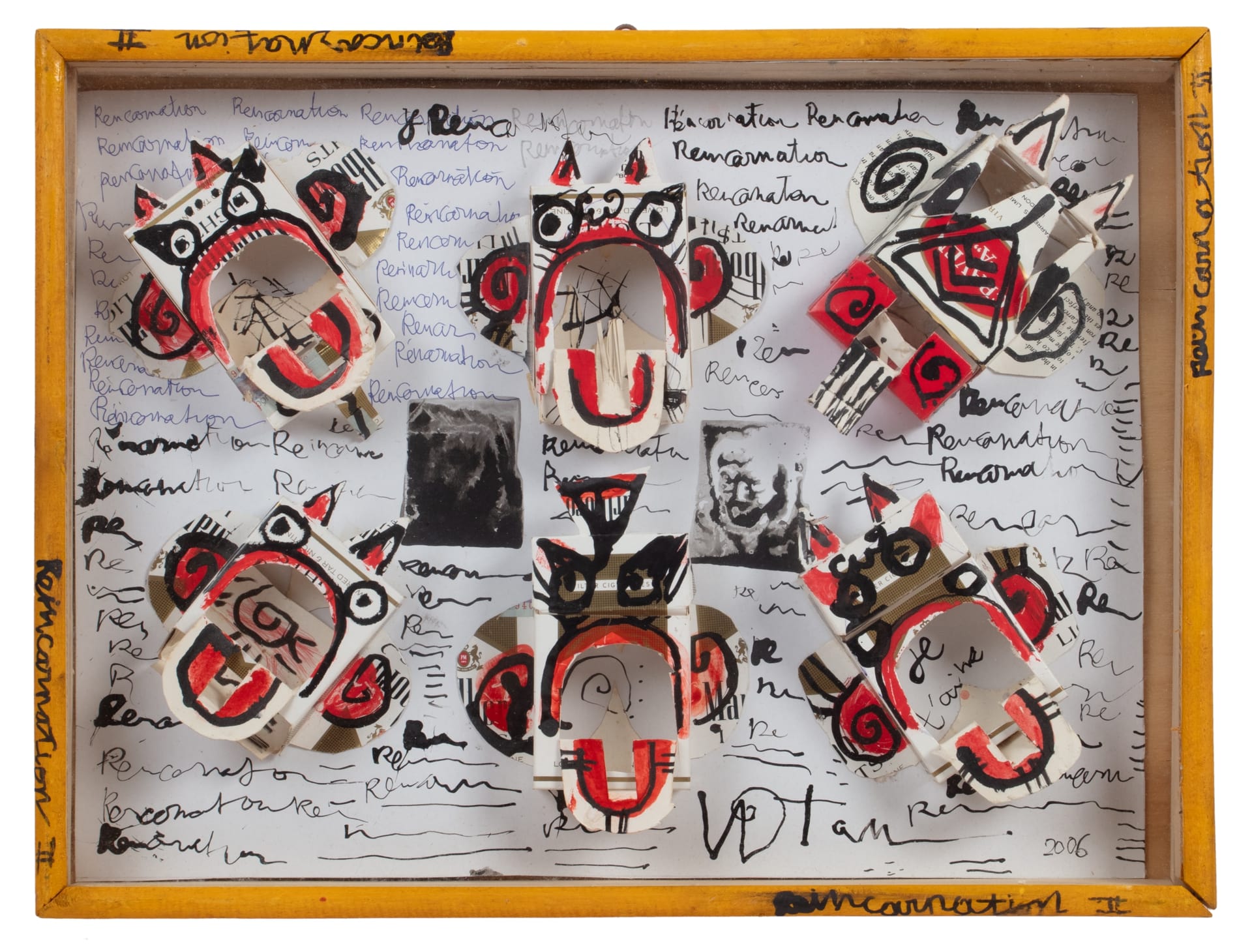

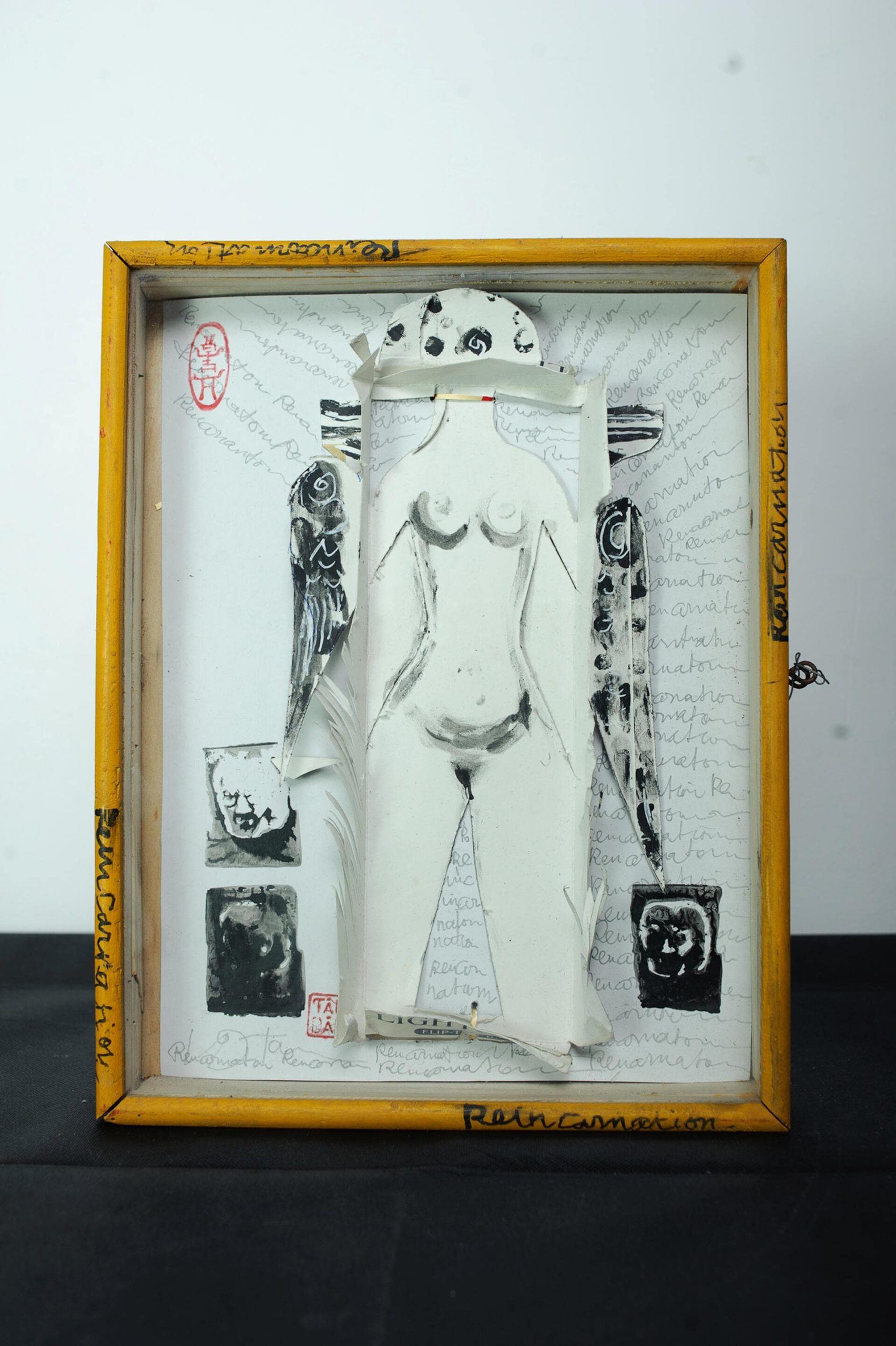

❝ Tân’s work could be described, at its most significant level, as talking back to used institutions. Perversely, his use of decoration relates to a connection between the individual and the state. His works deny the reality of their original materials and hence attempt to defy the increasing supremacy of the legitimate economy by recycling rubbish and turning it into new, real things that claim to be works of art…

Ian Howard. ‘Vietnamese Artists: Making Do, Digging In, Breaking Out’, catalogue of the 2nd Asia-Pacific Triennial of Contemporary Art, Queensland Art Gallery, 1996, p. 50

In his own private way, Tan confounds the inevitable and immutable processes of the world of objects by changing the value and meaning of already used things ❞

❝ Pilgrim’s glass-lidded boxes, containing cut-out cardboard packaging sculpture, exemplify the roving eye as they play with containment, display, protection, freedom, inclusion and exclusion. The series borrows its formally and conceptually fundamental display cases from Hanoi’s illicit street hawkers… The peddlers’ transgressive behaviour is an invisible but central tension of the work. ‘Suitcase of a Pilgrim’, in its allusion to citizen disobedience, flirts with subversion. Connected with this, the series also exposes ideas about private and public space, physical and psychological. The question of the encroachment of the state on individual rights and voice is relevant in Vietnam as elsewhere and Tan’s box series, in its lidded-case form, if not overtly political, manifestly toys with notions of control, boundaries, and by opposition, freedom. Its content too reinforces these ideas, small cardboard sculptures of insects and masks made by Tan from discarded cigarette and film boxes, icons that here speak of entrapment or altered identity. ❞

Iola Lenzi, “The Roving Eye. Southeast Asian Arts: Plural Views on Self, Culture and Nation”, catalogue of the exhibition “The Roving Eye. Contemporary Art from Southeast Asia”, ARTER, Istanbul, Turkey, 2014, p. 45